I have mentioned Dunston House/Estate before, however in preparing for a new historical plaque to mark the location of the site I have been conducting more research. This post documents some of that research. Please do note this is a brief account and some details may be left out. I plan to continue the research and produce a small booklet when I get to the stage I feel it tells most of, if not the whole, story in a clear and detailed way.

Origin of the name

Before delving into the estate, it is worth setting the scene. In the documented historical records, I have found numerous records of the name, which refer to an area or a field, including:

| Date | Name |

|---|---|

| 1547 | Dunstanefield and Dunstonefield |

| 1590 | Dunstones |

| 1603 | Dunstone Fielde |

| 1641 | Dunston |

| 1671 | Dunston Field |

| 1690 | Dunstone |

From later maps it would appear the field(s) was in the area of Mount Road. Then the house was built and called “Dunston House”. There are a few newspaper articles at the end of the 1700s that spell it with an ‘a’ along with a few maps. Officially though the house was most definatly Dunston. Well into the 1800s the area was still being called Dunston Park.

It has been suggested that the name may originate from Old English, the Saxon language. There is no evidence to support this locally, but it would fit. In Old English, “dún” referred to a hill or slope, while “stán,” pronounced as “stane,” means stone. This combination essentially described a stony slope or hill[1].

A background

The Winchcombe family had possessed the Manor of Thatcham for nearly 170 years. The Manor of Thatcham was sold to Henry St. John, Viscount Bolingbroke. Bolingbroke, having been attainted for high treason in 1715, had his estates seized and subsequently sold by the crown in 1722 through a private Act of Parliament. The Manor of Thatcham became the property of James Brydges, the Duke of Chandos, during the same year. He, in turn, sold it to Brigadier General Richard Waring. Shortly after acquiring the estate, General Waring had a mansion built on a section of his new manor known as Dunston.

Richard Waring

Richard Waring, from the Waring family of Waringstown in Co. Down, Northern Ireland, began his military career in 1690 when he joined the Earl of Danby’s Volunteer Regiment of Dragoons in London. He quickly rose through the ranks, becoming a lieutenant and the youngest captain of the Grenadier troop in 1691. He served in Holland, notably at the Battle of Steenkirk in 1692. His subsequent promotions included becoming Brigadier General in 1711 and Colonel of the Carabineers in 1715, before retiring from military service.

The Manor

In 1722, Waring acquired Thatcham Manor from the Duke of Chandos and subsequently commissioned the construction of a park and a house on a section of the manor known as Dunston. The exact duration of the construction is uncertain, but it appears to have been finished by 1725[2].

The drawing above is the only one I have come across of Dunston House. It was, Samuel Barfield notes, for upwards of a century (presumably since the house was to down) been in the possession of the family of Mrs Wheeler of Thatcham, whose ancestor was a servant in Sir John Croft’s establishment. I am yet to locate the original!

This new residence was named Dunston House and was characterized by its construction from glazed brick, with stone accents at the corners and arched windows. A park was designed around the house, featuring carefully planted trees. Part of the landscaped area was laid out in a pattern resembling the troop formations from one of the battles in which General Waring had previously fought. The house included:

- Principal story:

- A suite of elegant, well-proportioned rooms, including a State bed chamber and Dressing Room.

- A spacious saloon measuring 32 feet by 29 feet.

- A Drawing Room with dimensions of 36 feet by 25 feet.

- A Dining Parlour measuring 29 feet by 21 feet.

- A Library with dimensions of 21 feet by 18 feet.

- A Breakfast Parlour sized at 26 feet by 22 feet.

- Second story:

- Nine good bed chambers.

- Suitable dressing rooms.

- Upper story:

- Six servants’ rooms.

And there were other buildings including a brew house, stables and a dove house. Richard lived at the new house becoming not only Lord of the Manor of Thatcham but the first resident one since perhaps Saxon times.

Richard believe that Henwick was included in the Lordship and indeed, in my opinion it should have, you can read more on the topic in the post Reputed manor of Henwick. Thus a dispute broke out between Jemmett Raymond, who at the time owned the Henwick estate, and Waring as to the existence of Henwick as a manor. Raymond believed he owned the manor of Henwick and was such Lord of the Manor of Henwick. Waring though claimed there was no such manor, only the “Manor of Thatcham, otherwise Henwick” and as such Raymond had no claim. This dispute would go on for a long time, going to the Court of Chancery, the court eventually found in favour of Raymond.

Alice, the wife of Richard, passed away in 1730, and Richard himself followed in 1737. They were laid to rest in Thatcham parish church. Their son, William Ball Waring, then inherited the manor and estate, assuming the title of the new Lord of the Manor. William Ball Waring passed away in 1746, while his wife appeared to have remained at Dunston House.

Passing to the Crofts

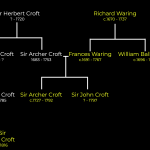

On the death of William Ball Waring the estate passed to the Croft family through his sister, Frances Croft (formerly Waring), and subsequently to her son, Sir Archer Croft.

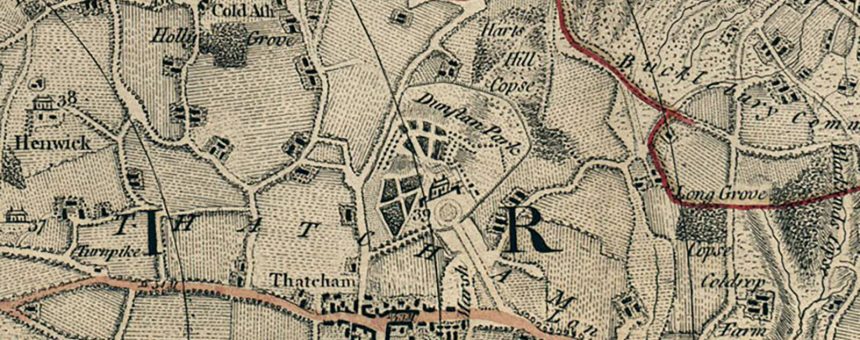

The map above is from 1768 by John Willis and is based on John Rocques map of 1761. Rocque, a French-born British surveyor and cartographer, is renowned for his map of London, published in 1746. In 1761, he conducted a survey of Berkshire. I have heard several say that Rocque compared the Dunston Estate to Blenheim Palace. I have not been able to find the source of this so for the moment assuming that to be a myth. However Rocque must have been impressed with Dunston House as he is recorded as describing it as “one of the most magnificent mansions in the country.“

It is not clear when the house was first leased out but William Young Ottley was apparently born there in 1771. Prior to the Ottley family the house had been leased to Henry Vansittert Esq. Going back to the Ottley family it was still with them in 1774, under the occupancy of Richard Ottley Esq. In the same year, the estate was once again put up for lease, featuring furnishings, a stock of deer, outbuildings, stables, fish ponds, and a Dove House[3].

In the publication “Mrs. Montague, Queen of the Blues: Her Letters and Friendships from 1762-1800“, Mrs. Montague makes note of events in 1778[4]. She recalls that around this time, the estate had been leased to a Naboob, but that Sir Archer Croft and his wife moved back in and sold the deer in the park. However, in 1780 another advert shows the deer in the park up for sale[5]; was the date wrong? Were there more deer? Montague goes on to say, with regard to the Archer Croft and his wife:

“the other evening they had some squabble, and my Lady set out alone, and on foot, towards Newbury. The Newbury Machine overtook her, she desired the Coachman to stop, and let her get in, he did not know her, and told her the Coach was full, then she said she wd ride on the box, a Civil man in the Coach said that by her dress and appearance she could not have been used to that mode of travelling, and he wd give her his place and go himself on the box, thus they arrived at the Pelican, where unknown she slept that night, and next day went to Reading, where she now is negotiating a separation. Thus do this unhappy pair give a Comedy to the Neighbourhood. I think her Ladyship must be un peu brusque, to go away in this manner.”

Mrs. Montague, Queen of the Blues, 1778

According to Montague one of the daughters then attended school in Thatcham so presumably Archer Croft was still at the residence. However, in 1780, the estate was put up for lease, again. Adverts continue in 1781 and appear again at the start of 1785[6][7]. But in December 1785 there is a record for Maria Ann Fitzroy being buried on 6th Dec. She was the daughter of Lord Euston who was resident at Dunston House. The family continued in sorrow as in 1787 they buried another child, Georgina Laura Fitzroy. It is not clear what is going on at this point, was the whole house leased out or was it only part of it, were there apartments the Crofts were staying in, or was something else going on? In 1790, a different family had taken residence at Dunston House, and it appears that they also experienced sorrow, as evidenced by another record mentioning Harriet, the daughter of Mr. Waddington, who was born at Dunston House but tragically passed away a few months later. However, their fortunes took a turn for the better the following year when their daughter Frances was born. In her later life, Frances would go on to become Baroness Bunson.

In a publication from 1792, “Topographical Survey of the Great Bath Road from London to bath and Bristol”, the author writes:

“Before we enter Thatcham, Dunsted Park, the seat of Sir A. Crofts, appears on the right. The house is a stately, regular mansion, well situated on the south side of a woody ridge, which screens it on the north. The grounds are pleasingly varied and well furnished with wood…“

Archibald Robertson, 1792

It was also noted that you could see right across the valley[8]. And yes it does say “Dunsted Park”, clearly a typo.

The downfall

An auction on 2nd March 1792 by William Davis saw an attempt to sell much of the assets of the estate including, all live and dead stock, wines, furniture, 24 cows, a bull, 130 ewes, 65 dozen port, sherry, wine, Mahogany card tables and much more[9]. Sir Archer Croft died 1792 and the estate passed to brother John who it is believed lived there. As what seems to have become an annual custom, records from 1795 and 1796 show that cattle were taken by other inhabitants into Dunston Park in May[10].

John Croft died in 1797 and with no male heir the estate passed to Kinsman, Rev. Sir Herbert Croft, grandson of Francis Croft. An auction followed selling off items that included Paintings, Books, Glass, China, Furniture, Horses, Wine, Pleasure boat, carriages, horses, farming stock and timber. Auctions continued throughout this and the following year with the entire estate being put up for sale ion 9th and 10th October 1798 in several lots. That was not the end though, it was up for auction again in 1800.

One of the auctioneers, George Robins, bought the land, and sold it afterwards in separate lots. The materials of the building were sold off, that is the actual building materials. For example wainscot floors, oak and fir timbers, marble chimney pieces, stone stair cases, clinker pavements, doors, lead. Mr. Wyatt, the agent of Lord Carrington, who was building his house at Wycombe, bought much of the oak flooring, Mr. Tull of Crookham bought some of the bricks and Dutch tiles.

Around 1802 William Mount purchased the Manor of Thatcham, and went on to own Henwick as well. There are various properties around Thatcham built from materials from the demolished house, perhaps the easiest to see is what we call today The United Reformed Church (URC). This was built in 1804 using glazed bricks, and other materials all from Dunston House and purchased by John Barfield. The map below gives an approximation of the location and area covered by the estate.

Later references

The name Dunston Park continued in use and appeared on many maps, sometimes as Dunston and others as Dunstan. Articles in the 1820s and 1830s still referred to Dunston House and/or Dunston Park. But there were variations with the ‘a’ creeping in now and again.

To confuse things further between 1880 and 1883 Dunstan Lodge was built in Station Road, later demolished for new houses and shops. Between 1900 and 1910 a new house was built just behind Bluecoat House. This house was called Dunstan House, perhaps the source of the confusion over the spelling today. The house remained until the 1970s when it was demolished.

Summary

Dunston House was Thatcham’s only Manor House and home to the Waring family and the Croft family who were the first resident Lords of the Manor since Saxon times. The house was a grand structure with a garden that would easily encompass the village/town at the time. The avenue from the main road (A4) to the front door was in excess of 800m. Little archaeological work has been undertaken[11]. As said at the start, this is a short version with bits missed out, I will continue the research and aim to share it when complete.

References

- [1] Tubb, R., Thatcham Road Names, Thatcham: 1991

- [2] Newbury Weekly News and General Advertiser, Thursday 24 September 1874

- [3] Reading Mercury, Monday 26 September 1774

- [4] Mrs. Montague, “Queen of the blues”, her letters and friendships from 1762-1800, Volume 2, Editted by R Blunt, New York: 1923

- [5] Reading Mercury – Monday 20 March 1780

- [6] Reading Mercury – Monday 05 February 1781

- [7] Reading Mercury – Monday 14 March 1785

- [8] Topographical Survey of the Great Bath Road from London to bath and Bristol, Archibald Robertson, 1792

- [9] Reading Mercury – Monday 27 February 1792

- [10] Reading Mercury – Monday 02 May 1796

- [11] Fitzpatrick, A. P. (2011). Early Iron Age ironworking and the 18th century house and park at Dunston Park, Thatcham, Berkshire. Berkshire Archaeological Journal 80. Vol 80, pp. 81-111.